Since Agni V’s first test in 2012, the world has eagerly awaiting its successor. VK Saraswat, the then-chairman of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), confirmed the development of a long-range ballistic missile one year hence. He also alluded to the capacity of numerous warheads to simultaneously strike multiple targets. At that time, the designs were complete and the project was in the hardware implementation phase.

On the Agni VI, there has been an unnerving silence over the past nine years since the remarks. Why is radio silence prevalent? Can India create a 10,000-kilometer-range intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM)?

Two sides of a same coin:

It is commonly assumed that a government with a successful space programme may target and employ nuclear bombs anywhere in the planet. If they can launch even a medium-sized satellite into a higher earth orbit, they can modify their space launch vehicles to effectively destroy any point on Earth. ISRO is the cornerstone of India’s successful space programme.

1980 saw the launch of India’s first satellite utilising the domestic SLV3 rocket. Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam initiated the development of ballistic missiles with the launch of the DRDO rocket. Using the knowledge and technology from the SLV3 rocket, India conducted the maiden test flight of its surface-to-surface Agni Technology Demonstration missile in less than a decade.

The first in the series, Agni I, had a range of 700-1,200 kilometres. After the success of Agni I, ISRO created the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) with four stages that utilised a combination of solid and liquid fuel. This innovation substantially influenced the design of the Agni II missile, particularly its second stage. The rocket has two stages powered by solid fuel. The mobility and adaptability of this 2-stage concept have been lauded. India could reach all of Pakistan and the majority of south-eastern China with a range of 2,000 kilometres.

Parallel to India’s breakthroughs in space technology, the Agni family of missiles was improved. India manufactured further Agni missiles, including the Agni III, which can go up to 3,500 kilometres, and the Agni IV, which can reach up to 4,000 kilometres.

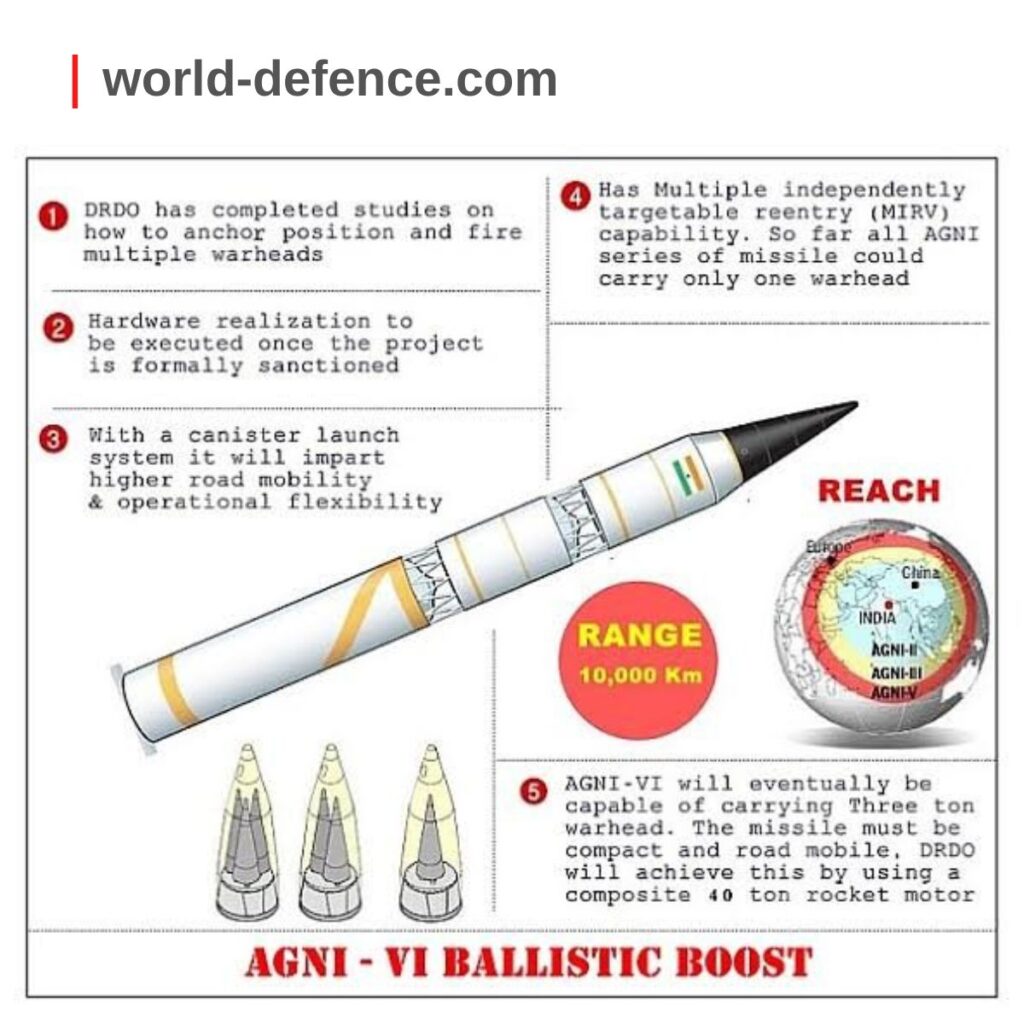

In 2012, the Agni V ICBM, with a range of around 5,500 kilometres, was a game-changer. Due to the higher payload and multiple independently-targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) capabilities of Agni V, India effectively displayed its counterforce capability. The lethality of the Agni V was augmented by their respective precision.

Clearly, this is a communication of a higher order sent to a potential foe. India has signalled to the rest of the world with the launch of Agni V that while it does not engage in preemptive nuclear attacks, it has preserved a counterforce capability. Therefore, if anyone utilises nuclear weapons against India, India can now launch a counterforce capability against its adversary’s nuclear attack forces. The successful launch of India’s Agni V missile continues to ruffle China’s feathers, which has claimed that India has intentionally understated its capabilities.

According to Chinese researchers, the missile is capable of reaching targets up to 8,000 kilometres away. However, according to Indian officials, the missile may travel beyond 5000 kilometres.

The Extraordinary Case of Agni VI

The United States believes India may turn the PSLV into an intercontinental ballistic missile with a significant boost in range within a year. Due to India’s indigenous space programme, the majority of the components required for an ICBM are currently accessible in India.

Dr. Christopher, the head of the DRDO, indicated in 2018 that the organisation is capable of building an ICBM capable of striking targets over 10,000 kilometres away. He also disclosed that the organisation was developing a surface model and a subterranean variant. According to him, when the United States, the United Kingdom, and other nations barred the import of laser technology components, India was able to build its own and has been self-sufficient in this field ever since.

If the nation is therefore capable, why has it not been developed? The possibility exists that India does not want its western allies to be concerned. Since neither the United States nor the majority of Europe are within the Agni V’s strike range, there is minimal cause for alarm. When India was authorised to join the Missile Technology Control Regime, this became painfully evident (MTCR).

If India showcases an intercontinental ballistic missile with the range to strike vital cities around the world, the allies may have a different opinion. Effective range of ballistic missiles is a topic of intense dispute. Numerous Europeans and Americans are of the opinion that India does not need to create an intercontinental ballistic missile with a range of 10,000 kilometres, as its most distant foe is China, which it can hit with its current capabilities. If India publicly acknowledges the Agni VI and its range of more than 10,000 kilometres, the United States and European nations will be furious.

However, many in India contend that if China is permitted to develop ballistic missiles with ranges greater than 10,000 kilometres, then India has no reason to be left behind.

Since the launch of the Agni V missile in 2012, India has had the ability to test its anti-satellite missile. Nonetheless, it was examined in 2019. Even in 2019, India’s anti-satellite missile stunned the international community, with only Russia and the United States supporting the nation. The Pentagon informed the Senate Armed Services Committee that India’s anti-satellite weapons test was conducted out of concern for space threats. It was the optimal time for India to conduct the test so as not to alarm its friends. Most likely, Agni VI is experiencing the same situation.

The geopolitical holdup discourages the immediate testing of India’s intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) without alarming its Western partners.

The sun is supposed to be the codename for Agni VI. It was exhibited at IIT Kanpur, proving its presence, and DRDO scientists have never denied the existence of this programme. It is safe to infer that India possesses an ICBM with a range of above 10,000 kilometres. The crucial question is when India will test the Agni VI. Will it occur in the following three years?