Agnikul Cosmos, the Chennai-based space start-up, which builds small rockets, is set for a test launch by December-end in a sub-orbital level at 50 to 60 km from the Earth from ISRO’s Satish Dhawan Space Research Centre at Sriharikota. “We hope to start commercial launches from the second quarter of 2023,” said Srinath Ravichandran, Co-Founder and CEO of the company, which was incubated at IIT-Madras.

The company has raised around $15 million since its inception in December 2017, and plans to soon raise another $20 million with existing investors participating in it, Ravichandran told businessline. The current investors include Mayfield India, PI Ventures, Specialie Invest, Beenext, Artha Venture Fund, Lets Venture, CIIE, Globevestor and LionRock (Srihari Kumar). Anand Mahindra is also on board the company as a major investor, he said.

“We have accomplished all of the sub-system development, and know each of the systems independently. We are now putting the vehicle together to make the integration process work smoothly, so that we can start attempting the launches,” he said. The test launch is to prove all the core technologies, he added.

The company’s focus is to enable space transportation with low lead time. “We want to go to space within a two-week time frame as against the present waiting time of 18-24 months to launch small satellites. The only way to go to space is with the right share and finding the right partner. It is like waiting for a bus in a bus stop; there should be space in the bus to take you to the right place,” he said.

The company operates out of the IIT-Madras ecosystem, with multiple facilities in and around Chennai for 3D printing rocket engines, a testing facility and assembly facility.

Ravichandran said the company’s customers will be anyone who is building a small satellite and wants to go to Low Earth Orbit. The focus is on a class of satellite that is less than 300 kg in mass because the company’s rocket can put them in space quicker. “We do that with 2-3 technologies, including 3D printing by making rocket engines with a single piece system and the vehicle is configurable. This means, it can be expanded or can be shrunk depending on the satellite that’s taken to space,” he said.

The satellites can be launched from a mobile launch pad. This is an important factor to enable quick launches, he said.

Ravichadnran said the company’s two-stage rocket is a liquid propulsion with the combination being kerosene (Aviation Turbine Fuel) and liquid oxygen (cryogenic). The rocket will go to LEO of 500-600 km where there is the maximum commercial interest. The sub-orbital level is for test launch to prove that things work smoothly, he said.

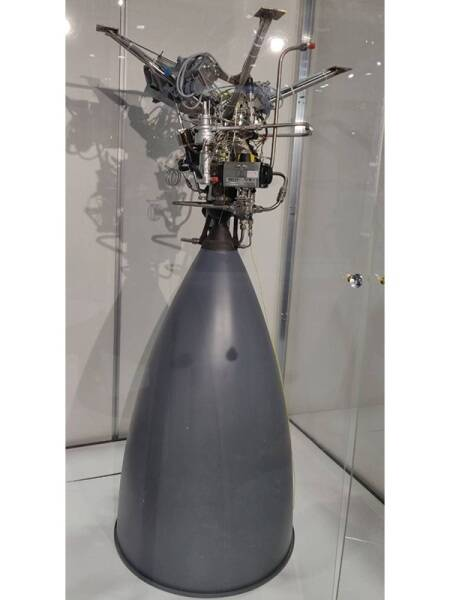

Everything in the vehicle is designed inhouse. Validating those in a flight is a key milestone. Agnikul successfully test fired its single piece 3D printed engine – Agnilet Vertical Test Facility, Thumba Equatorial Rocket Launching Station (TERLS), at Vikram Sarabhai Space Center (VSSC), Thiruvananthapuram. With the support of IN-SPACe and ISRO, the test was conducted to validate the technological possibility that rocket engines can be made as a single piece of hardware.

On competition from others, Ravichandran said that rocket business is a logistics business and there is room for many players. It is a like a truck business. ‘Here, we make the truck and drive the truck,” he said. The amount of weight that goes to the orbit is the deciding factor, and the customer is charged based on per kg basis, he added.

Globally, around 100 tonnes is going just in small satellites every year with maximum number of launches happening in the US. However, they are not able to get enough rockets. This provides spaces to lot of players to come in. “With Skyroot (based on solid propulsion) and Agnikul being both Indian companies, the comparison comes in. While they are operating in the 500 kg class, we operate in less than in 300 kg class. It is important to focus on this class to filling the gap of fleet. While ISRO’s lowest capacity is 300 kg while ours stops at 300 kg. We also feel that small satellites are where the business is,” he said.

Agnikul Cosmos has developed what it claims is the world’s first single-piece 3D-printed rocket engine.

Earlier this month, Chennai-based space-tech startup Agnikul Cosmos successfully completed the test firing of Agnikul—the company’s 3D-printed rocket engine—at the Vikram Sarabhai Space Center in Thiruvananthapuram. Agnilet claims to be the world’s first single-piece 3D-printed rocket engine.

The Agnilet rocket engine is designed to be used in Agnibaan—a small satellite launch vehicle that can carry payloads of up to 300 kilograms to a low-Earth orbit—which the company is currently developing. The Agnilet rocket engine is a “semi-cryogenic” engine. It uses a mixture of liquid kerosene at room temperature and supercold liquid oxygen to propel itself.

Srinath Ravichandran, co-founder and CEO of Agnikul, explained to indianexpress.com that “3D printing is a sweet spot for launch vehicles,” emphasising how it can be used to manufacture multiple iterations of complex and customised designs, speeding up the research and development process.

“When you use older manufacturing techniques, there is a lot more complex hardware and manpower involved. With 3D printing, you can make hardware nearly as fast as you can make software. This is why we were able to make hundreds of iterations of the design so that we could finally reach a stage where we can 3D print an entire engine in one shot,” said Ravichandran over a video interaction.

But 3D printing is not without its disadvantages. While it does allow engineers to reiterate designs faster than with conventional manufacturing techniques, it is not as scalable. With conventional techniques, once a design has been set, multiple copies can be manufactured much faster.

“3D printing is still slow if you compare it to injection moulding or planar-based manufacturing where you can manufacture millions of pieces every month. So it is not meant for manufacturing in large volumes. But rocket engines and a lot of the components of launch vehicles can be manufactured using this method,” explained Ravichandran.

However, Agnikul sees the successful test-firing of the Agnilet engine as a validation for using the technology for space-based applications. “The engine is very complex and it functions at very high temperatures. So if we can 3D print an engine successfully, that makes us very confident about manufacturing simpler, static parts for the rest of the launch vehicle,” he added.

But for an actual space launch, it is not just the engine that needs validation. Other systems, including avionics packages and guidance and navigation systems, also need to be tested and validated. Agnikul is working on validating the entire launch vehicle and is hoping to have a test launch by the end of the year. During the test launch, the Agniban rocket will be carrying payloads that are designed to test its systems.

In-SPACE’s help

The Indian government established the Indian National Space Promotion and Authorisation Centre (In-SPACE) in 2020 as a single-window autonomous agency under the Department of Space.

Over the last year or so, the regulator has emerged as a focal point for easing communication, integration, and permission-related complexities between government and private space players.

This was also evident in Agnikul Cosmos’ engine test at VSSC.

“To conduct any test with and at ISRO, a lot of interfaces have to be figured out. There is a lot of effort involved in making sure that an engine which has been made in some other place can interface with ISRO’s test facilities,” Ravichandran said.

As a result, there is a lot of back and forth, paperwork, and so on, he explained.

Three key players were involved in this test: the Department of Space, ISRO, and Agnikul Cosmos. In-SPACE ensured that Agnikul Cosmos had everything necessary for ISRO to allow the startup to test at their facility. It also ensured that the startup’s requirements in relation to the test were met.”So there is no framework that’s available for taking some engineering hardware that has not been built at ISRO to test at an ISRO facility. So there needs to be a lot of interfacing and In-SPACE has become that face interfacing for us. We are not running and talking around to 10 different entities within ISRO,” he added.